Back

On jobs to be done

Introduction

I recently read Competing Against Luck: The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice by Taddy Hall. It offers insight into the Jobs to be Done theory and why customers purchase certain products or services.

The central premise is this: customers don't buy products or services; they pull them into their lives to make progress. We call this progress the "job" they are trying to get done, and in this metaphor we say that customers "hire" products or services to solve these jobs.

When you understand this concept, the idea of uncovering consumer jobs make intuitive sense. However, the definition of "Job to be Done" is precise. It's worth taking a step back to unpack the elements to develop a complete theory of jobs.

Progress

The book defines a "job" as the progress that a person is trying to make in a particular circumstance. This definition of a job is not simply a new way of categorizing customers on their problem. It’s key to understanding why they make the choices they make.

The choice of the word “progress” is deliberate. It represents movement toward a goal or aspiration. A job is always a process to make progress; it’s rarely a discrete event. A job is not necessarily just a “problem” that arises, though one form the progress can take is the resolution of a specific problem and the struggle it entails.

Circumstance

The idea of a “circumstance” is intrinsic to the definition of a job. A job can only be defined—and a successful solution created—relative to the specific context—in which it arises. Think about the milkshake example. The reason why you purchase a milkshake is different based on the context or "circumstance" (i.e., is it in the morning on the way to work when you're bored, or when you're with your child and you want to be a good father by letting them have a treat?).

There are dozens of questions that could be important to answer in defining the circumstance of a job. “Where are you? “When is it? Who are you with? While doing what? What were you doing half an hour ago? What will you be doing next? What social or cultural or political pressure exert influence?" And so on.

This notion of a circumstance can can extend to other contextual factors as well, such as life stage (just out of college? Stuck in a midlife crisis? Nearing retirement?) married status (married, single, divorced, newborn baby, young children at home, adult parents to take care of?) or financial status (underwater in debt, ultra-high net worth?) just to name a few.

The circumstance is fundamental to defining the job (and finding a solution for it), because the nature of the progress desired will always be strongly influenced by the circumstance.

The emphasis is on the circumstance is not hair-splitting or simple semantics—it is fundamental to the Job to be Done.

Functional, social and emotional complexity

Finally, a job has an inherent complexity to it: it not only has functional dimensions, but it has social and emotional dimensions, too.

In many innovations, the focus is often entirely on the functional or practical need. But in realty, consumers’ social and emotional needs can far outweigh any functional desires. Think of how you would hire childcare. Yes, the functional dimensions of the job are important—but the social and emotional dimensions probably weight more heavily on your choice. “Who will I trust with my children?”.

What is a Job?

To summarise, the key features of the definition are:

A job is the progress that an individual seeks in a given circumstance.

Successful innovations enable a customer’s desired progress, resolve struggles, and fulfill unmet aspirations. They perform jobs that formerly had only inadequate or non-existent solutions.

Jobs are never simply about the functional—they have important social and emotional dimensions, which can even be more powerful than the functional ones.

Because jobs occur in the flow of daily life, the circumstance is central to their definition and becomes the essential unit of innovation work—not the customer characteristics, product attributes, new technology, or trends.

Jobs to be Done are ongoing and recurring. They’re seldom discrete “events.”

What isn't a Job?

A well-defined job offers a kind of innovation blueprint. This is very different from the traditional marketing concepts of “needs” because it entails a much higher degree of specificity about what you’re solving for.

Needs are ever present and that makes them necessarily more generic. “I need to eat” is a statement that is almost always true. “I need to feel healthy, or “I need to save for my retirement” — those needs are important to consumers, but their generality provides only the vaguest of direction to innovators as to how to satisfy them.

Needs are like trends—directionally useful, but totally insufficient for defining exactly what will cause a customer to choose one product or service over another.

Simply needing to eat isn’t going to cause me to pick one solution over another—or even pull any solution into my life at all. I might skip a meal. And needs, by themselves, don’t explain all behaviour: I might eat when I’m not hungry at all for a myriad of reasons.

Jobs take into account a far more complex picture. The circumstances in which I need to eat, and the other set of needs that might be critical to me at that moment, can vary widely.

Think back to our milkshake example. What will cause me to choose the milkshake are a bundle of needs that are in play in those particular circumstances.

That bundle includes not only needs that are purely functional or practical (”I’m hungry and I need something for breakfast”), but also social and emotional (”I’m alone on a long, boring commute and want to entertain myself, but I’d be embarrassed if one of my colleagues caught me with a milkshake in my hand so early in the morning.”)

In those circumstances, some of my needs have higher priority than others. I might, for example, opt to swing into the drive though (where I won’t be seen) of the fast-food chain for a milkshake for that morning commute.

But under different circumstances—I have my son with me, it’s dinnertime, and I want to feel like a good dad—the relative important of each of my needs may cause me to hire the milk shake for an entirely different set of reasons. Or to turn to another solution to my job altogether.

Many wonderful inventions have been, unwittingly, built only around satisfying a very general “need.” Take for example, the Segway. In spite of the media frenzy, the Segway was a flop. It had been conceived around the need of more efficient personal transportation. But whose need? When? Why? In what circumstances? What else matters in the moment when somebody might be trying to get someplace more efficiently?

The Segway was a cool invention, but it didn’t solve a Job to be Done that a lot of people shared. Very few people felt compelled to pull the Segway into their lives.

On the other hand of the spectrum from needs are what we call the guiding principles of my life—overarching themes that are ever present, just as needs are. I want to be a good husband, a valued member of my community, I want to inspire my students, and so on. These are critically important guiding principles to the choices I make in my life, but they’re not my Jobs to be Done. Helping me feel like a good dad is not a Job to be Done. It’s important to me, but it’s not going to trigger me to pull one product over another into my life. The concept is too abstract.

A company couldn’t create a product or service to help me feel like a good dad without knowing the particular circumstances in which I’m trying to achieve that. The jobs I am hiring for are those that help me overcome the obstacles that get in the way of making progress toward the themes of my life—in specific circumstances. The full set of Jobs to be Done as I go through life may roll up, collectively, into the major themes of my life, but they’re not the same thing.

Shifting the competitive landscape

It’s important to note that we don’t “create” jobs, we discover them. Jobs themselves are enduring and persistent, but the way we solve them can change dramatically over time.

Think, for example, the job of sharing information across long distances. The underlying job hasn’t changed, but our solutions for it have: from Pony Express to telegraph to air mail to email and so on. For example, teenagers have had the job of communicating with each other without the nosy intervention of parents for centuries. Years ago, they passed notes in the school hallway. But in recent years, teens have started hiring Snapchat, which could not have even been imaged a few decades ago.

The creators of Snapchat understood the job well enough to create a superior solution. But that doesn’t mean Snapchat isn’t vulnerable to other competitors coming along with a better understanding of the complex set of social, emotional, and functional needs of teenagers in particular circumstances. Our understanding of the Job to be Done can always get better. Adopting new technologies can improve the way we solve Jobs to be Done. But what’s important is that you focus on understanding the underlying job, not falling in love with your solution for it.

For innovators, understanding the job is to understand what consumers care most about in that moment of trying to make progress. Understanding the circumstance-specific hiring criteria triggers a whole series of important insights.

Here’s an example. When a smoker takes a cig break, on one level he’s simply seeking the nicotine his body craves. That’s the functional dimension. But that’s all that’s going on. He’s hiring cigarettes for the emotional benefit of calming him down, relaxing him. And if he works in a typical office building, he’s forced to go out to a designated smoking area. But that choice is social, too—he can take a break from work and hang around with his buddies. From this perspective, people hire Facebook for many of the same reasons. They log onto Facebook during the middle of the workday to take a break from work, relax for a few minutes while thinking about other things, and convene around a virtual water cooler with far-flung friends.

In some ways, Facebook is actually competing with cigarettes to be hired for the same Job to be Done. Which the smoker will choose will depend on the circumstances of his struggle in that particular moment.

Managers like to keep their framing of competition simple. Coke versus Pepsi. Playstation versus Xbox. Butter versus margarine. This conventional view of the competitive landscape puts tight constraints around what innovation is relevant and possible. Through this lens, opportunities to grab market share seem finite.

But from a Jobs to be Done perspective, the competition is rarely limited to products that the market chooses to lump into the same category. CEO Reed Hastings made this clear when recently asked by if Netflix was competing with Amazon. “Really, we compete with everything you do to relax. we compete with video games. We compete with drinking a bottle of wine. That’s a particularly tough one! We compete with other video networks. Playing board games.”

The competitive landscape shifts to something new, maybe uncomfortably new, but one with fresh potential when you see competition through a Jobs to be Done lens.

Think of the path ahead through the lens of Jobs Theory. Each company will have to understand the Job to be Done in all of its rich complexity. Then they’ll have to consider and shape their offerings around the experiences that consumers will seek in solving their jobs—and help them surmount any roadblocks that get in their way of making progress. Competitive advantage will be granted to whoever understands and best solves the job.

Big hire v little hire

The moment a consumer brings a purchase into his or her home or business, that product is still waiting to be hired again—we call this the “Little Hire.” If a product really solves for the job, there will be many moments of consumption. It will be hired again, and again.

A woman may buy a new dress, but she doesn’t really consume it until she’s actually cut the tag off and worn it. It’s less important to know that she chose blue over green than it is to understand why she made the decision to finally wear it over all other options.

How many apps do you have on your phone that seemed like a good idea to download, but you’ve more or less never used them again? If the app vendor simply tracks downloads, it’ll have no idea whether the app is doing a good job solving your desire for progress or not.

Jobs to be done have always existed. Innovations have just gotten better and better in the way we can respond to them. So no matter how new or revolutionary your product may be, the circumstance of struggle already exist. Consequently, in order to hire your new solution, by definition customers must fire some current compensating behaviour or suboptimal solution—including firing the solution of doing nothing at all.

Companies don’t think about this enough. What has to get fired for my product to get hired? They think about making their product more and more appealing, but not what it will be replacing.

A customer’s decision-making progress about what to fire and what to hire is complicated. There are always two opposing forces battling for dominance in that moment of choice and they both play a significant role.

The forces compelling change to a new solution: First of all, the push of the situation—the frustration or problem that a customer is trying to solve—has to be substantial enough to cause her to want to take action. A problem that is simply nagging or annoying might not be enough to trigger someone to do something differently. Secondly, the pull of an enticing new product or service to solve that problem has to be pretty strong, too. The new solution to her Job to be Done has to help customers make progress that will make their lives better. This is where companies tend to focus their efforts, asking about features and benefits, and they think, reasonably, that this is a roadmap for innovation. How do we make our product incredibly attractive to hire.

The forces opposing change: There are two, unseen, yet incredibly powerful forces at play that companies ignore completely: the forces holding a company back. First, “habits of the present” weigh heavily on consumers. “I’m used to doing it this way.” Or living with the problem. “I don’t love it, but I’m at least comfortable with how I deal with it now.” And potentially the more powerful than the habits of the present is, second, the anxiety of choosing something new. “What if it’s not better?”

Consumers are often stuck in the habits of the present—the thought of switching to another solution is almost too overwhelming. Sticking with the devil they know, even if imperfect, is bearable.

Think of it this way: the Job to be Done has to have sufficient magnitude to cause people to change their behaviour—”I’m struggling and I want a better solution than I can currently find”—but the pull of the new has to be much greater than the sum of the inertia of the old and the anxieties of the new.

No matter how frustrated we are with our current situation or how enticing the product is, if the forces that pull us to hiring something don’t outweigh the hindering forces, we won’t even consider hiring something new.

FedEx is now a household name, but breaking into the market might have seemed impossible decades ago. But through a job lens, it makes sense. When competitors successfully enter markets that seem closed and commoditised, they do it by aligning with an important job that none of the established players has prioritized.

Purpose brands provide remarkable clarity. They become synonymous with the job. A well-developed purpose brand will stop a consumer from even considering looking for another option. They want that product. And they will pay premium prices for it.

FedEx illustrates how successful purpose brands are built. A job has existed practically forever: the “I need to send this from here to there—as fast as possible with perfect certainty” job. Some US customers hired the US Postal Service’s airmail; a few desperate souls paid couriers to sit on airplanes. But because nobody had yet designed a service to do this job well, the brands of the unsatisfactory alternative services became tarnished when they were hired for this particular purpose. But after FedEx specifically designed its service to do that exact job, and did it wonderfully gain and again, the FedEx brand began popping into people’s minds.

This was not built through advertising. It was built through people hiring the service and finding that it got the job done. FedEx became a purpose brand—in fact, it became a verb in the international language of business that is inextricably linked with that specific job.

A helpful framework

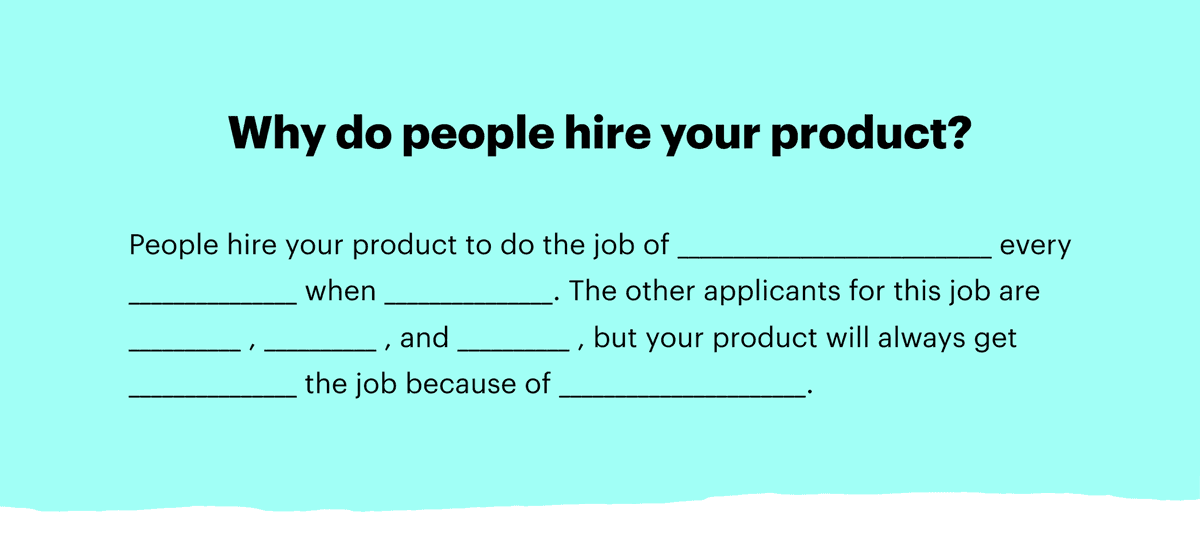

Why do people hire your product? if you can frame your product like this, a lot of decisions around growth and what to build become super clear: